Transformations as the Backbone of a Modular MLOps Pipeline

Poor code organization leads to "pipeline spaghetti," where data ingestion, cleaning, feature engineering, and modeling code are tangled together. This tangle often arises when code is developed in a linear fashion (for example, in one giant notebook) rather than separated into reusable modules for each pipeline stage. The result is code that is hard to test or reuse.

Transformations as the Backbone of a Modular MLOps Pipeline

Note: This article references the academic demonstration version of the pipeline.

Some implementation details have been simplified or removed for IP protection.

Full implementation available under commercial license.

Introduction

Poor code organization leads to “pipeline spaghetti,” where data ingestion, cleaning, feature engineering, and modeling code are tangled together. This tangle often arises when code is developed in a linear fashion (for example, in one giant notebook) rather than separated into reusable modules for each pipeline stage. The result is code that is hard to test or reuse.

Without logical separation, experiments cannot be iterated quickly because even small changes require running or understanding the entire pipeline. A lack of modularity also undermines collaborative development, since multiple people cannot easily work on different pipeline components in parallel.

These anti-patterns contrast with recommended software engineering practices: modular, well-documented code with consistent naming conventions is much easier to maintain than “thousands of lines of spaghetti code.”

1. Avoiding Monolithic Transformations

Modular transformations help prevent large, unmanageable blocks of code. Each transformation is often reduced to a single core step with standardized inputs and outputs-such as providing a DataFrame plus a typed configuration object and returning an updated DataFrame. This practice keeps the codebase transparent, testable, and easier to iterate upon. See configs/transformations, and dependencies/transformations for details on how each transformation is defined in this project.

2. Consistency Through Single-Source Configuration

Transformations work hand in hand with structured configurations (YAML plus Python dataclasses). Each configuration strictly defines relevant parameters and enforces type consistency. When DVC detects a change in either the transformation code or its config, it triggers only that transformation step, saving time and maintaining reproducibility.

3. Clear Naming Conventions and “Don’t Repeat Yourself”

A best practice is to give each transformation a base name shared by: dependencies/transformations/mean_profit.py

- The Python module (e.g., `mean_profit.py`) for each transformation consists of:

- The dataclass (e.g.,

MeanProfitConfig) - The function (e.g.,

mean_profit)

- The dataclass (e.g.,

- The config file (e.g., `mean_profit.yaml`)

This approach results a single source of truth for each step. Rather than scattering parameter definitions or helper functions across multiple places, the pipeline references one module and its associated config.

4. Example: Mean Profit Transformation

Python Module

# dependencies/transformations/mean_profit.py

import logging

from dataclasses import dataclass

import pandas as pd

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

@dataclass

class MeanProfitConfig:

mean_profit_col_name: str

mean_charge_col_name: str

mean_cost_col_name: str

def mean_profit(

df: pd.DataFrame,

mean_profit_col_name: str,

mean_charge_col_name: str,

mean_cost_col_name: str,

) -> pd.DataFrame:

df[mean_profit_col_name] = df[mean_charge_col_name] - df[mean_cost_col_name]

logger.info("Done with core transformation: mean_profit")

return df

Hydra Config

# configs/transformations/mean_profit.yaml

defaults:

- base

- _self_

# One root key with the name of the transformation - The unique identifier for it.

mean_profit:

mean_profit_col_name: mean_profit

mean_charge_col_name: mean_charge

mean_cost_col_name: mean_cost

This mean_profit module demonstrates how each transformation resides in a dedicated Python file, with a dataclass for parameters and a function that applies the transformation. A separate YAML file (e.g., mean_profit.yaml) mirrors these parameter names, ensuring a direct mapping between code and config.

5. Integration with a Universal Step and DVC

Version Control for Code and Data

A scripts/universal_step.py script can import both the dataclass and function. It instantiates the dataclass with parameters from the configs/transformations/mean_profit.yaml YAML file, then calls the transformation dependencies/transformations/mean_profit.py. Meanwhile, DVC treats each transformation as a separate stage, referencing that same base name in dvc.yaml (via overrides, deps and outs). When any detail of the transformation changes-be it in the code or the config, or the input/output file(s), or the metadata file - DVC reruns only that step without invalidating the entire pipeline.

This ensures that for every single execution a snapshot is created for each referenced file by DVC. Rollbacks are easy to perform, and any guesswork regarding which parameter values were used for any previous execution is eliminated. DVC maintains a cache under .dvc/cache/.

Every time a stage in dvc.yaml is executed, a snapshot of the state of all included files is taken.

Practical Example

This section showcases how one transformations is defined and ran. It underlines the importance of dvc.yaml. Stage dependencies/transformations/mean_profit.py is used in the following.

Running a Single Stage

All it takes to run the stage mean_profit is:

dvc repro --force -s v3_mean_profit

Using a hydra config group and config code duplication is kept to a minimum. Updates in dvc.yaml are defined in This is the final stage defined in dvc.yaml, and only there. One source of truth.

The great part about defining most parameters by referencing a few values from keys that need to be set at runtime via overrides is that the only overrides needed are:

script_base_name=mean_profit

transformations=mean_profit

data_version_input=v3

data_version_output=v4

stages:

# Formatted for readability

v3_mean_profit:

cmd: python scripts/universal_step.py \

setup.script_base_name=mean_profit \

transformations=mean_profit \

data_versions.data_version_input=v3 \

data_versions.data_version_output=v4

desc: Refer to deps/outs for details.

deps:

- ./project/scripts/universal_step.py

- ./dependencies/transformations/mean_profit.py

- ./configs/data_versions/v3.yaml

outs:

- ./data/v4/v4.csv

- ./data/v4/v4_metadata.json

Adding a Transformation to dvc.yaml

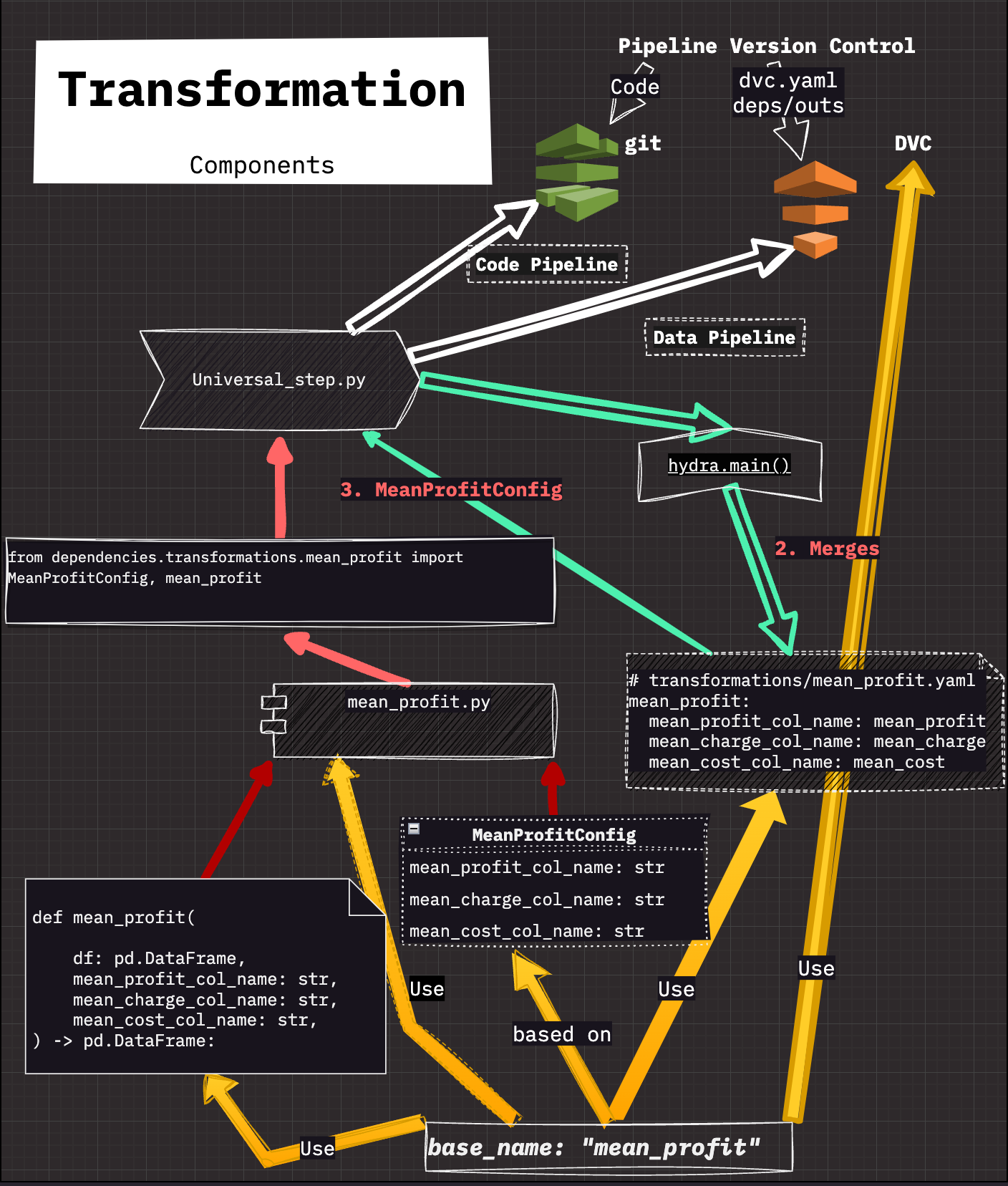

Transformation Components Overview

The diagram illustrates how each transformation flows through the pipeline:

- Code Pipeline: Maintains the universal step script and the transformation modules (like mean_profit), versioned in Git.

- Data Pipeline: Uses DVC to track input and output data, referencing transformation stages in dvc.yaml.

- Config Reference: Each transformation has a YAML file that matches its base name and feeds parameters into the dataclass. The universal step handles these parameters and invokes the correct function.

- Single Source of Truth: There is exactly one Python file and one config file for each transformation, preventing duplication and confusion.

Conclusion

Transformations structured in this manner reduce complexity, maintain clarity, and improve reproducibility. Consistent naming, typed configurations, and separate stages per transformation are all best practices that keep the pipeline maintainable over time. By adopting this approach, teams can evolve individual transformations without risking unwanted side effects in unrelated parts of the codebase.

Video: Transformations as the Backbone of a Modular MLOps Pipeline

© Tobias Klein 2025 · All rights reserved

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/deep-learning-mastery/